Olivia explores the past and what life was like for Māori communities, including her own whānau, to help to develop her story.

My book has two timelines, one is the 1960’s – 70’s and the other is 2010. It is the story of a family and how events from the past reverberate through time.

To prepare to write the book I did a lot of research about Māori moving to Wellington in the 60’s and 70’s. I concentrated on the influx of rural Māori into the city, the reasons for it and the Ngāti Poneke Maori Club, of which my maternal grandparents were foundation members.

I read a lot of books, academic papers and articles; and I watched documentaries and footage from the New Zealand archives. I also interviewed many, many people, including most of my family.

My father went to Te Aute College and the reason he, his brothers and many other impoverished Māori, were educated in private schools was because of the intervention of the Reverend Dan Kaa. He was an amazing man, writer and classics scholar, who made it his mission to get as many Māori educated as he could.

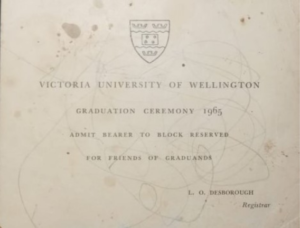

My father was one of the very few Māori at Victoria University in the 60’s. He studied at night as he had three jobs. He told me that failure was not an option for him. He also said that when he told people he was going to Varsity they laughed. My father told me that only one Māori woman graduated the year he got his degree. That woman, whoever she was, was an inspiration to me.

My mother flatted on Tinakori Road, with her sisters, down the road from my Dad, who flatted with his brothers. She worked at Tolls and said that she would spend all her money on clothes and go to Dad’s flat to eat, as the boys, as she called them, always had food. Dad said food was a real priority and they grew up with nothing and spent a lot of their childhood farmed out to relations or prowling the land like starving animals.

There was a lot of racism. One time my dad, his brother and cousin went to Hastings to pick fruit to make some money for his sisters wedding and no one would rent them rooms, so they had to sleep under a bridge. Bill Nathan from Ngāti Poneke told me that he couldn’t take his wife Donas with him when looking for a flat as most landlords did not rent to Māori and he looked Pākehā enough to get away with it.

My research was steeped in heartbreak. It was hard to look at what my people faced. The pictures it conjured were of struggle and hardship but also laughs, drinking, parties, balls and dances and taking care of one another in an alien environment.

It is impossible to get all the research I had accumulated into my novel. In fact I could hardly shoehorn any of it in. But it is all sitting in my heart, feeding the story, so I guess it’s all in there anyway.